I came across many amusing T-shirt slogans and stickers at Skepkon 2025. One in particular stuck in my mind:

Admitting that you don’t know something is actually a banal and simple statement – completely independent of any religious context. And yet many people find this difficult to do. Instead, they cling to certain beliefs, no matter how high the mountain of contradictory facts piles up in front of them. Some people, however, do not exhibit this behaviour and are able to honestly shrug their shoulders when they don’t know something. They are intellectually humble.

Recognising the limits of one’s own knowledge

Intellectual humility is a concept that is being studied in various psychological disciplines and is considered a potential remedy for social division. It describes the ability to recognise and accept one’s own cognitive limitations. In other words, intellectually modest people have no problem openly admitting, ‘I don’t know everything, and what I do know may be wrong. And that’s okay.’ Intellectual modesty has both social and individual benefits that are important in various contexts:

- It promotes social cohesion and reduces group polarisation.

- People with higher intellectual humility show more tolerance towards opposing political and religious views.

- Higher intellectual humility is associated with empathy, forgiveness and a willingness to cooperate with others.

- Intellectually humble people are less inclined to devalue or insult others.

- Intellectual humility is positively associated with academic achievement and knowledge acquisition.

- It supports decision-making and learning by improving the ability to distinguish between strong and weak arguments.

- They show a greater willingness to learn from mistakes and develop further.

- Intellectual humility is also associated with greater life satisfaction and less negative affect.

Sounds good, right? If even a small amount of humility has so many potential positive effects, a simple question arises: Why do many people find it so difficult to acknowledge the limits of their own knowledge?

The problem lies less in admitting one’s own limitations and more in the second component of intellectual humility, namely the willingness to adjust one’s own beliefs when new facts and evidence suggest that the previous ones are partially or completely wrong. This requires the ability to separate one’s ego from personal beliefs.

The crux of the matter is therefore less about rationality than identity: some beliefs have a deep personal significance for us. They are closely linked to our self-image, our social belonging and status — and it is precisely these interconnections that make it extremely difficult to allow doubt.

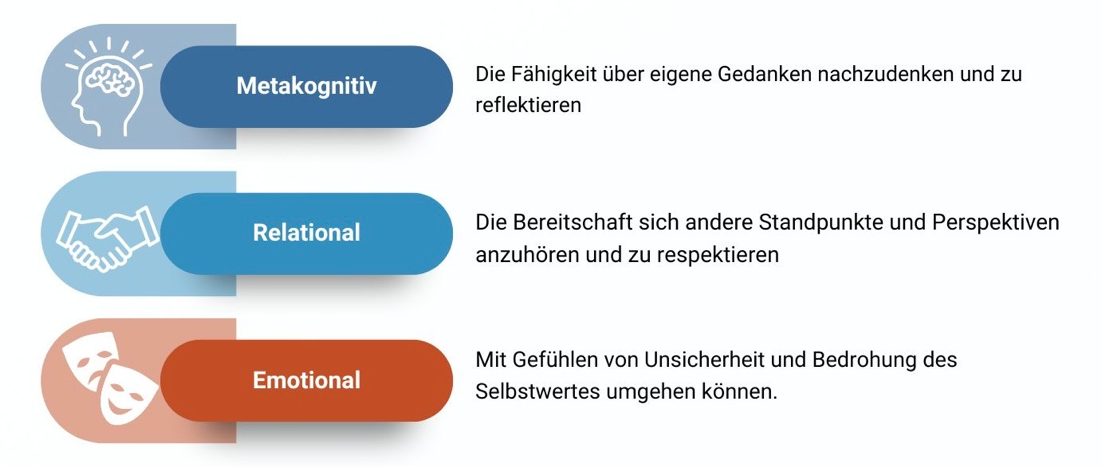

Intellectual humility is therefore more than just saying, ‘I know I can be wrong.’ It is a quality that requires several components:

People with high intellectual humility do not show excessive self-confidence not only because they recognise their own fallibility, but also because respect for other points of view is incompatible with claims of infallibility. They do not confuse their convictions with their own ego and are therefore able to tolerate the uncertainty that comes with the possibility that even central assumptions could be wrong.

However, it is precisely this way of dealing with uncertainty and ambiguity that is difficult for many people, as doubts about their own world view are quickly experienced as a personal threat.

The link to critical thinking

Critical thinking is broadly described in psychology in two ways: firstly, as a collection of specific skills (e.g. examining information in a structured manner and questioning it in a targeted way) and dispositions (e.g. open-mindedness and perseverance when faced with difficult problems), and secondly, as a complex, active cognitive process that involves analysing, evaluating and synthesising information in order to form sound judgements and solve problems.

According to this understanding of the term, critical thinking influences whether and how willingly we abandon and adapt old knowledge and beliefs. Intellectual humility, on the other hand, influences how effectively we can apply our critical thinking skills in the first place. Curiosity and openness to new ideas are considered characteristics of critical thinkers, but open-mindedness does not automatically mean that one also takes into account the limits of one’s own knowledge.

Modesty is, so to speak, one level higher. Paradoxically, even those who are skilled in critical thinking can diminish this ability if they are too convinced of their knowledge and cognitive abilities. This tendency to overestimate one’s own abilities is known as the Dunning-Kruger effect. The tricky thing about it is that people are often blind to their own overconfidence. It is much easier to spot errors in others’ thinking than to recognise and address gaps in one’s own beliefs. This phenomenon is aptly called bias blind spot.

People with high intellectual humility tend to be more open to information that contradicts their beliefs and devote more time and attention to analysing such evidence. Instead of viewing other perspectives as threatening, they approach them with curiosity. This attitude promotes cognitive flexibility – the ability to reorient one’s thinking when new information does not fit with previous beliefs. This is crucial for avoiding confirmation bias: the tendency to preferentially seek evidence that supports one’s own assumptions and to ignore contradictory information. Intellectual humility can therefore improve critical thinking because perspective-taking reduces the likelihood of falling into these cognitive traps. It can also curb excessive self-confidence by promoting self-reflection.

In addition to the term used here, there is also a broader concept of critical thinking, particularly in philosophy. This includes intellectual humility in the form of a sincere reservation of error. In this article, however, we use the narrower psychological term explained above.

What does science say?

The above assumptions have also been confirmed by empirical research in recent years.

- Stronger critical thinking: In a study, students with high intellectual humility consistently performed better in critical thinking. This advantage was evident regardless of whether the problems were social or mathematical (Fabio & Suriano, 2025).

- More accurate thinking & less overconfidence: People with high intellectual humility perform better in critical thinking tests and are less likely to overestimate their abilities. Particularly striking: those with very low ID tend to exhibit the Dunning-Kruger effect – i.e., massive overconfidence (Bowes et al., 2024).

- Better handling of misinformation: Intellectual humility helps to distinguish more clearly between true and false news, without this being merely due to excessive caution. People with high intellectual humility also recognise more accurately when they themselves are right or wrong – an indication of better metacognitive insight (Prike et al., 2024).

- Trust in science & less climate scepticism: People who are intellectually humble have more trust in science and show less scepticism about climate change – regardless of age, education or political orientation. The willingness to correct beliefs and respect other perspectives is particularly crucial in this regard (Huynh et al., 2025).

- Perspective-taking as a reinforcing factor: Empathising with others can increase intellectual humility, while an exclusively self-centred view weakens it. Actively practising perspective-taking also reduces feelings of offence when one’s own views are challenged. However, intellectual humility does not automatically protect against confirmation bias – even intellectually humble people can search for information selectively (Kotsogiannis et al., 2024).

- Cognitive foundations: Intellectual humility is linked to cognitive flexibility and intelligence. Both can strengthen the ability to recognise one’s own errors and adjust attitudes. Interestingly, these factors have a compensatory effect: high flexibility can compensate for low intelligence and vice versa (Zmigrod et al., 2019).

- Less polarisation: People with high intellectual humility show less political and religious polarisation. The ability to separate one’s ego from one’s beliefs seems to be particularly effective in this regard. At the same time, the findings suggest that intellectual humility alone is not enough to completely curb polarisation (Bowes & Tasimi, 2025).

- Less political myside bias: Intellectual humility is associated with a lower tendency to evaluate arguments one-sidedly in favour of one’s own political beliefs. This effect was evident across various political issues and regardless of political orientation (Bowes et al., 2022).

- More prosocial behaviour: Intellectual humility is associated with greater empathy, gratitude, helpfulness and fairness, and is accompanied by less power-seeking behaviour. Characteristics such as recognising one’s own limitations, a non-defensive approach to one’s own beliefs and respect for other points of view form the basis for this (Krumrei-Mancuso, 2017).

Practical significance and limitations

Overall, the findings show that intellectual humility improves the ability to revise beliefs and promotes critical evaluation of information. It can thus not only improve the quality of our thinking as a whole, but also strengthen our ability to deal constructively with uncertainty and differences of opinion. The key to this is not a single skill, but a combination of self-reflection, cognitive flexibility and respect for other perspectives.

Intellectual humility plays a potentially important role in promoting critical thinking by supporting cognitive flexibility and openness to new information. In particular, its potential to reduce extremist views and polarisation makes it a skill of inestimable social value.

This has several possible implications for practice:

- Social and professional contexts: Promoting intellectual humility through, for example, training and reflection programmes could lead to better decision-making processes and more constructive interactions.

- Education: Integrating intellectual humility into educational programmes and developing curricula could support critical thinking from an early age and protect against polarisation in the long term.

- Training perspective-taking: Interventions that specifically practise perspective-taking (e.g. role-playing, structured dialogue formats) could be an effective means of increasing intellectual humility – both in educational settings and in professional contexts.

However, it should be borne in mind that intellectual humility has its limitations. It can be impaired by various personal, interpersonal and cultural factors, such as:

- Cognitive biases: People tend to seek confirmation of their beliefs (confirmation bias, myside bias). This selective choice of information makes it difficult to clearly recognise one’s own limitations and errors.

- Dealing with uncertainty: Intellectual humility requires the ability to tolerate and accept uncertainty. People who find this difficult prefer simple, clear-cut answers and tend to think in black and white terms, which limits their openness to alternative perspectives.

- Social dynamics: Group identity can suppress intellectual humility, as group solidarity is often placed above facts. Those who identify strongly with a political, religious or cultural community are often motivated to defend its ‘truth’ in order to secure closeness and status. Loyalty to the group can thus override epistemic accuracy.

- Cultural contexts: Collectivist societies with a stronger emphasis on social cohesion (e.g. China, Japan) tend to promote more context-sensitive thinking and thus intellectual humility. Societies that emphasise individualism (e.g. the USA) tend to favour rigid, egocentric thinking.

Conclusion

We all have prejudices and make mistakes. Intellectual humility is not a panacea, but it is an important tool for addressing these problems. It is therefore less an academic virtue than an attitude that is equally indispensable for social cohesion and healthy scepticism.

In short, you don’t have to go as far as Socrates and make ‘I know that I know nothing’ your new philosophy of life. ‘I don’t know everything and am therefore open to other perspectives’ is perfectly sufficient.

References:

Bowes, S. M., Costello, T. H., Lee, C., McElroy-Heltzel, S., Davis, D. E., & Lilienfeld, S. O. (2022). Stepping outside the echo chamber: Is intellectual humility associated with less political myside bias?. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 48(1), 150–164.

Bowes, S. M., Ringwood, A., & Tasimi, A. (2024). Is intellectual humility related to more accuracy and less overconfidence?. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 19(3), 538–553.

Bowes, S. M., & Tasimi, A. (2025). How intellectual humility relates to political and religious polarisation. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 20(4), 569–581.

Fabio, R. A., & Suriano, R. (2025). Thinking with humility: Investigating the role of intellectual humility in critical reasoning performance. Personality and Individual Differences, 244, 113251.

Huynh, H. P., Stanley, S. K., Leviston, Z., & Lilley, M. K. (2025). Intellectual humility predicts trust in science and scientists and climate change scepticism. Personality and Individual Differences, 246, 113366.

Kotsogiannis, F., Spentza, I., & Nega, C. (2024). The effects of perspective taking on intellectual humility and its relationship to confirmation bias. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society (Vol. 46).

Krumrei-Mancuso, E. J. (2017). Intellectual humility and prosocial values: Direct and mediated effects. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 12(1), 13–28.

Porter, T., Elnakouri, A., Meyers, E. A., Shibayama, T., Jayawickreme, E., & Grossmann, I. (2022). Predictors and consequences of intellectual humility. Nature Reviews Psychology, 1(9), 524–536.

Prike, T., Holloway, J., & Ecker, U. K. (2024). Intellectual humility is associated with greater misinformation discernment and metacognitive insight but not response bias. Advances in Psychology, 2, e020433.

Shah, R. (2025). Exploring the suppression of intellectual humility in honour cultures. Bachelor thesis, purl.lib.fsu.edu.

Zmigrod, L., Zmigrod, S., Rentfrow, P. J., & Robbins, T. W. (2019). The psychological roots of intellectual humility: The role of intelligence and cognitive flexibility. Personality and Individual Differences, 141, 200–208.

Deutsch (Deutschland)

Deutsch (Deutschland)  English (United Kingdom)

English (United Kingdom)